|

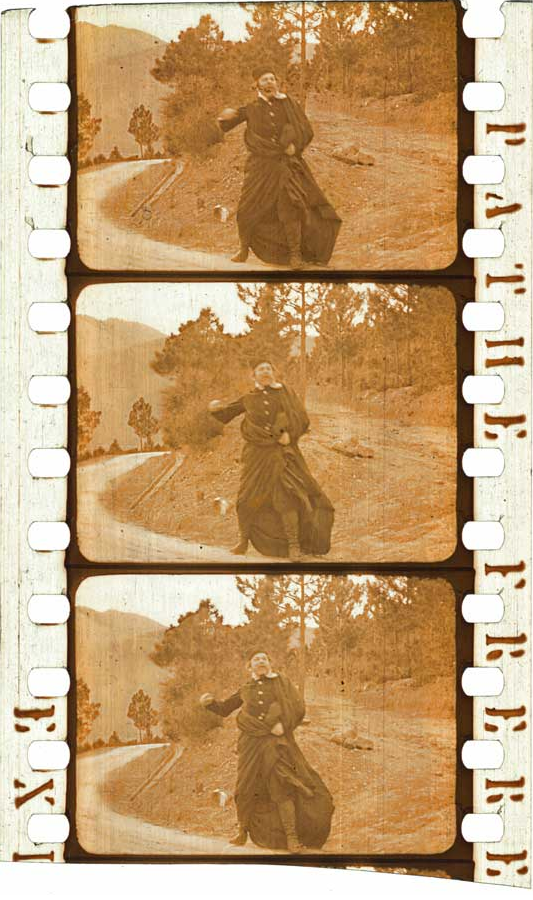

Back in the mid-1950’s through the early 2000’s, if you had visited almost any projection booth in the world,

you would have discovered that each projector had two and only two lenses.

One was labeled “FLAT” and the other was labeled “SCOPE.”

Those were misnomers.

Neither term was official.

“SCOPE” was an abbreviation of “Cinemascope,” and what it meant in practice was anamorphic,

meaning that the image on the film was squeezed, and that to unsqueeze the image, one needed to put the anamorphic lens on the projector.

“FLAT” meant only that the film was not “SCOPE.”

Where the term “FLAT” came from, I do not know.

Nonetheless, labs regularly printed “FLAT” or “SCOPE” onto every leader and tail.

Why, I do not know.

It didn’t help.

The labs could just as well have printed “MOVIE,” for all the good it did.

In my experience, the leaders never provided the information I needed:

filming, printing, and projection formats; number of channels; or “LET SOUND PLAY OUT AFTER END OF FINAL REEL”; and so forth.

For a “FLAT” film, the regular spherical lens would be used —

“spherical” because each lens element had surfaces that were sections of perfect spheres.

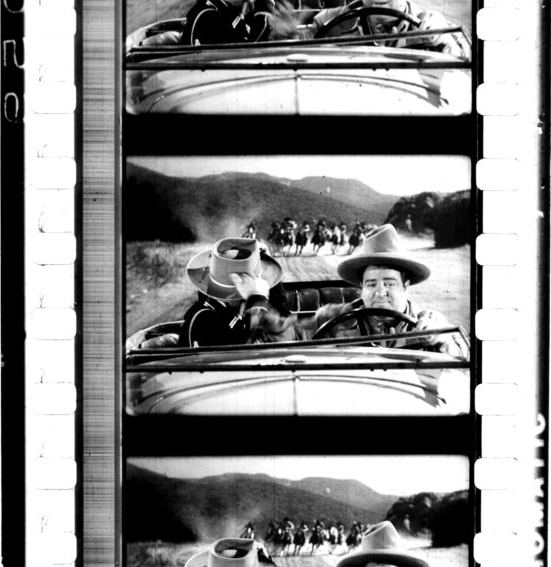

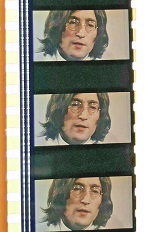

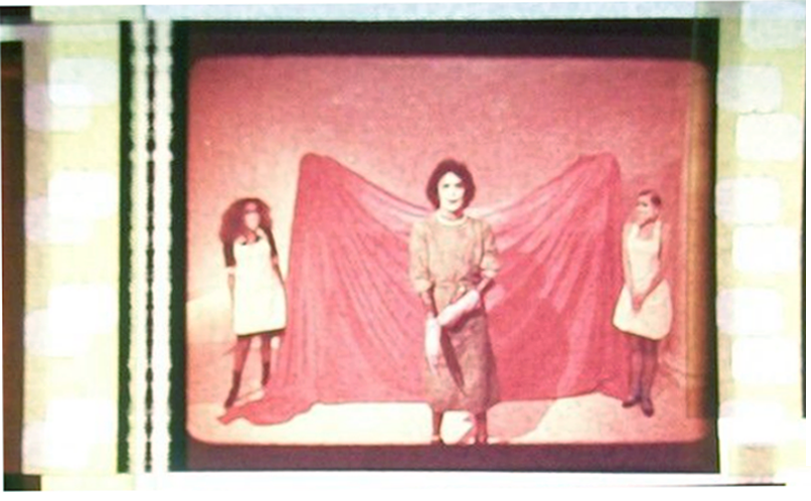

All five examples in the top row would be considered “FLAT,”

and so projectionists would crop and project them all exactly the same way.

“Anamorphic” could be done with prisms or, much more often,

with supplements that consisted of lens elements whose surfaces were sections of perfect cylinders.

Rare was the projectionist who knew any of this.

Rarer still was the projectionist who knew that there were numerous variations of both “FLAT” and “SCOPE.”

Pretty much any projection booth on the planet had only one “FLAT” setting and only one “SCOPE” setting,

and if the film on view that day did not match one of those two settings, tough.

The screening would be totally ruined — and yet NOBODY knew the difference. Except for me.

If you rushed to the booth in a panic and told the projectionist,

“You’re running it with the wrong aperture!,”

the projectionist would have just looked at you with a blank expression and said,

“What? It’s flat.”

They didn’t know.

Literally, they didn’t know.

If a distributor sent out a precaution,

“Please run this at 1:1.375.

If you do not have a 1:1.375 setting, please let us know and we shall assist,”

the manager’s dismissive response would be, “Yeah, sure,”

and then the manager would ask the projectionist,

“What was that all about?”

“I don’t know. It runs okay. I don’t see a problem.”

By the late 1950’s, or certainly by about 1960,

Western Europe jumped on the bandwagon and started shooting many (not all!) of its films with a 1:1.66 mask in the camera.

British films similarly were mostly composed for a 1:1.66 crop, but if they were financed by Rank, they were generally 1:1.75.

(The Rank cinema chain, so I am led to understand, cropped all taller films to 1:1.75 as a matter of policy.

According to Jack Theakston and Bob Furmanek in “The New Era of Screen Dimensions,” beginning in

1967, most UK films were composed for a 1:1.85 crop.

That is according to studio documentation. I disbelieve that studio documentation.

I have eyes and that is not what my eyes told me.

Yes, a few British films were best when cropped at 1:1.85, but those were generally the ones funded by Hollywood.

Others are just far too tight at that crop. The crop works, but it is distinctly uncomfortable.)

Australia was in lock-step with Rank and composed its films for a 1:1.75 crop.

When Hollywood collectively decided upon 1:1.85 as a standard,

Western Europe would not budge any further and just stuck to 1:1.66 — except for Italy, of course,

which did whatever Hollywood wanted.

So, from sometime around 1960 to, I think, the early 1990’s, Western European films were mostly 1:1.66, usually masked in the camera,

though 1:1.375 was certainly still used upon occasion and a few films were definitely 1:1.75.

(Yes, to answer an old question, the lab cropped

Last Tango in Paris to 1:1.75 in the printer and it looked perfect that way.

What the camera aperture was, heaven only knows.

The DVD is 1:1.85 and that is probably why the scene of the footbridge is noticeably cropped at the top.)

I am certain that you know why most Italian films at the time were shot at 1:1.85 (usually masked in the camera).

Right?

You know the answer, I’m sure you do.

Can’t think of the answer, though?

Come on, if you’ve read this far, then you are almost certainly a movie buff and all movie buffs should know the answer to this question.

Yes?

Give up?

Okay.

Hollywood was largely financing Italian movie production

by means of “unaffiliated” overseas subsidiaries, front groups, tax havens, and write-offs.

So Rome had to obey orders and format its movies the way Hollywood wanted them formatted.

Many of those “Italian” movies were made specifically for the US market.

That’s why so many Italian movies had Hollywood and London stars and that’s why so many of them were filmed partly or entirely in English.

Hollywood liked to use Italian production companies as front groups,

because these “Italian” movies cost only the smallest fraction of the price of proper Hollywood movies.

Besides, the Italian officials were so easily bribable and they were hardly assiduous about such silly little trifles as auditing and taxes and whatnot.

Thanks to these subterranean financial loopholes,

the Roman movie business was flooded with Hollywood dollars, with endless supplies of cash left over,

which provided the Fellinis and Viscontis and Pasolinis and whatnot with essentially free money.

That is how and why, for about twenty years, Italian filmmakers created what was probably the most impressive string of brilliant movies

that came out of any country at any time.

Ah, the accidental benefits of corruption!

Sadly, the Italian government cracked down in late 1975 and that was the end of that.

The Soviet Union, in the meantime, could not be bothered about such extreme cropping and continued using 1:1.375.

Its satellite countries in Eastern Europe did the same — often, not always.

With a few maddening exceptions, Hollywood, from the early 1960’s, was mostly 1:1.85,

though not all the other formats went extinct and even a few major Hollywood releases between 1963 and 1985 were 1:1.375

(Gizmo,

Brother Can You Spare a Dime?,

The Jetsons — The Movie,

An American Tail,

All Dogs Go to Heaven,

The Land before Time,

The Atomic Café,

Bugs Bunny Superstar,

One from the Heart).

My memory is that

New York, New York was 1:1.66;

and that

The Boys in the Band and

Taxi Driver were composed for a 1:1.66 crop.

Dr. Strangelove was, as its title, rather strange.

It was composed for a 1:1.75 crop, much of it was matted in the lab at 1:1.66,

but producer Kubrick sent out instructions that it be projected at 1:1.375 so that the black bars would show at the top and bottom.

Kubrick also seemed to prefer that the black bars show on screen for

Lolita, which was shot at various apertures, the smallest being 1:1.66.

There were others, too, but I can’t think of them off hand.

Oh, there is one I can think of, though it was independent, made outside the Hollywood system:

Coming Apart.

Parts were shot full-aperture and parts were shot with the Academy aperture,

and it was designed for projection at 1:1.375.

Since no cinema in the Western world could accommodate that,

the lab adjusted the result,

printing some shots too high and others too low, to keep the action on a 1:1.66 screen.

The 1:1.66 crop hurt the film.

I ran it at 1:1.375 and madly adjusted the framing knob up and down to compensate for the lab’s reframing.

Foolishly, the DVD was cropped to 1:1.66.

Dumb, dumb, dumb, dumb, dumb, dumb.

Oh, and

Faces, enlarged from 16mm,

was definitely framed for 1:1.375 and should not be cropped;

but that, too, was made outside the Hollywood system.

Then, in 1986, when HDTV was tentatively set for 5×3,

Hollywood studios decided to conform and replaced the guidelines in their viewfinders with new ones set for 1:1.66,

but didn’t tell anybody.

Cinematographers (yes, I met some) insisted they were composing for 1:1.85, not realizing that they were simply following the new markings,

which were actually 1:1.66.

Not a single cinema in the US changed its setting, though, and continued to crop everything to 1:1.85,

and nobody in management or in the audience could tell the difference.

I cannot imagine that people would have cared even if they could tell the difference.

In 1991, when the revised standard for HDTV was definitively set at 16×9,

Hollywood decided to rebel and, for a little while, the majority of Hollywood films were anamorphic.

(That was a strange sight in 1991, I thought, as I was in the booth of an 8-plex, seeing an anamorphic lens on almost every machine.

That was something new. Prior to that time, anamorphic films were the exception, not the rule.)

In the early 1980’s, Italy switched back to 1:1.66,

and Hollywood did the same in 1986.

Yet after Hollywood and Italy switched back to 1:1.66,

much of the rest of the world, for the first time ever, switched to 1:1.85 with masks in the camera.

As for what’s happening nowadays with digital projection,

I do not know, because I no longer go to movies.

What I learned from a knowledgeable projectionist is that

professional digital projectors (unlike home digital projectors)

all overscan, without exception, and thus crop every movie.

This is courtesy of something needlessly carried over from analogue television called a “safe area.”

This setting cannot be adjusted away.

(“Knowledgeable projectionist” sounds like an oxymoron,

sort of like a miniature giant or an enormous midget or a caring psychopath or un uomo d’onore.

Yet, I confess, there are a few knowledgeable projectionists.)

On the film |

TV safe area |

Current-day safe area

Professional digital cinema projectors

all crop somewhere between those two inner rectangles |

Now, to set the record straight, most of Russ Meyer’s films from 1968 onwards were indeed composed for a 1:1.85 crop.

Yes, they were shot with taller apertures in the camera, but, if you have eyes to see, the intended crop is unmistakable,

regardless of what his estate insists.

Now, to set the record straight, not all of Pasolini’s movies are 1:1.85,

regardless of what the now-defunct Pasolini Foundation insisted.

Now, to set the record straight, full-frame Silent 1:1.33 and Academy 1:1.375 are not the same thing at all, not even close.

Now, to set the record straight, most early talkies should never be cropped to Academy 1:1.375.

Now, to set the record straight, yes, Academy 1:1.375 has bars at the top and bottom of the frame.

So there.

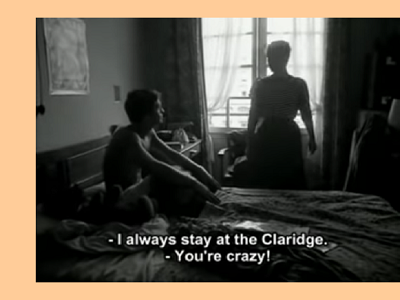

Breathless

Proper presentation:

Academy 1:1.375

projector aperture .600"×.825" |

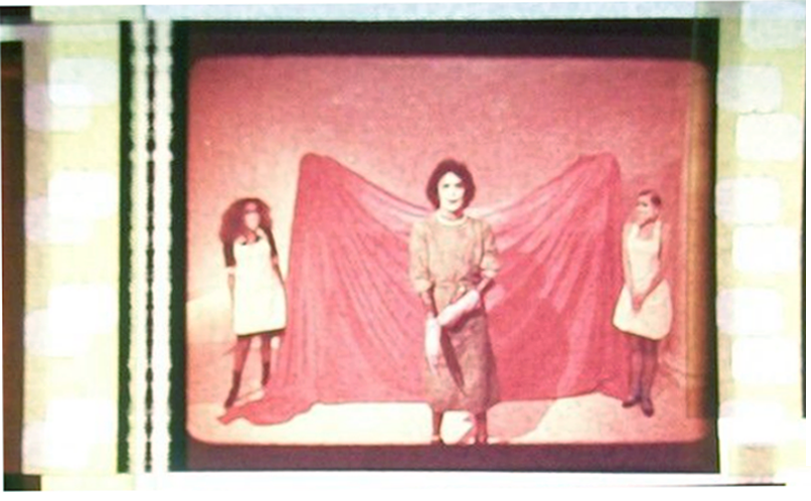

Breathless

As cropped at modern American cinemas:

US widescreen 1:1.85

projector aperture .446"×.825" |

The Man Who Loved Women

Proper presentation:

European widescreen 1:1.66

projector aperture .497"×.825" |

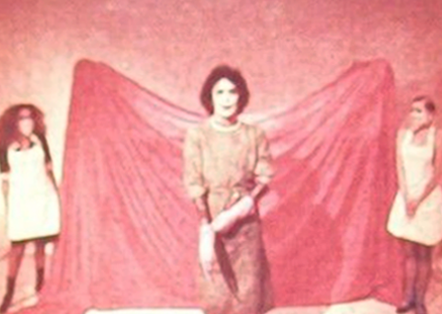

The Man Who Loved Women

As cropped at modern American cinemas:

US widescreen 1:1.85

projector aperture .446"×.825" |

Nobody, but nobody, ever understood why this irritated me.

Everybody, but everybody, was irritated with me for griping about this.

Typical reactions: “Why do you care?” “What difference does it make?” “Who cares?”

And, of course, my favorite reaction: “Oh, knock it off already! It looks fine!!!!!”

|

Text: Copyright © 2019–2021, Ranjit Sandhu.

Images: Various copyrights, but reproduction here should qualify as fair use.

If you own any of these images, please contact me.

|