Chapter 46

Escape

Escape

Back to the cinema: I did not inspect or project

Open City, because I was in Muskegon that week for the Busterfest,

but I KNOW I inspected almost every other film in that series,

even though I have no memory of having done so.

What I especially enjoyed about this film series were the after-film discussions.

They were unlike any other movie discussions I had ever heard.

I would sit in the auditorium mesmerized by the intelligence of the comments.

They changed my thinking about cinema, and about narrative.

It was such a delight to be in an audience of people who so sincerely cared.

I never expect to have such an experience again.

I remember that one of the programmers was deeply frustrated by the discussion that followed a showing of

A Night at the Opera, which was a terrible movie, though it did have a laugh or two.

(I wish they had booked The Cocoanuts instead.)

The next day, he sent out an email blast telling us what he wished he had said the night before,

and, again, I was just stunned.

His analysis was brilliant.

Backing up a bit: One evening, when I was inspecting an upcoming film,

I noticed that

In the Mirror of Maya Deren was being shown on Screen 6, cropped to 1:2.00.

I asked the assistant manager, “Why are you running Maya Deren in widescreen?”

She didn’t think it made a difference.

I fixed that up immediately, as best I could, under the circumstances.

Only the top masking moved.

Anamorphic was centered, but 1:2.00 was filed out of frame, deliberately too high.

I would need to file a new 1:1.375 aperture to match, but there was no time.

I pulled the aperture plate out so that it would cover only the soundtrack,

and I let the black bars on the film serve as their own masking.

I found a lens long enough to serve as a prime that would screw onto my zoom extender.

That night I borrowed the aperture and did an all-too-hasty cutting-and-filing job to get the center hole something vaguely like Academy,

but I goofed and made it a little bit too tall.

So for the last two and a half nights of its one-week run, the audience got to see pretty much the entire image.

I don’t remember why, but for some reason I needed to speak with the distributor of In the Mirror of Maya Deren,

and so I phoned the office, which, if memory serves, was in NYC.

I mentioned to the gal who took my call that, just before the one-week run came to an end,

I managed to set it up for Academy 1:1.375.

She didn’t understand why it wasn’t run that way all along.

I explained that there was hardly a cinema anywhere in the Western world that was set up to show 1:1.375 anymore.

She was surprised, and said, “That’s not good, because lots of our movies are Academy aperture.”

How could a distributor not know that?

When it came to Rope! (Screen 8),

sorry, I didn’t know about it until too late, and so audiences saw it cropped to 1:2.00.

It was dreadful.

I saw just a moment: a close-up of a face, but all that showed on screen was the nose.

Why didn’t the audience stage a riot, an armed protest, something?

When it came to White Heat on Screen 8,

I did not know until the final night, and so I improvised a make-shift solution to get the full Academy image onto the screen.

I kept the top masking down, pulled an Academy aperture from another machine,

and found an even longer lens to serve as a backup to the zoom to get a matchbook-sized image in the middle of the anamorphic setting.

Then a different group did the Irish series (Screen 3).

Then a different group did a Hollywood-retrospective series (Screen 1).

Then another friend did a 1962 series (Screen 2), and he later did a second series (Screen 6).

Then a women’s group did a women-filmmaker series (Screen 2).

Since all the prints were about as old as I was, but far more brittle than I was,

I decided to do the nice thing and volunteer my services.

This was now more than a full-time job, and for what?

Just to be nice.

I would do it again if such a situation were to arise again.

If I were to socialize, such situations would arise again,

and that’s why my social circle these days consists solely of my cat.

Would it not have been easier, overall, for the staff to be properly trained

and for the booth to be properly equipped?

In the world of cinema, that’s asking for far too much.

Oh, the women’s group, the women’s group, the women’s group,

I must tell you an anecdote about one film in the series put on by the women’s group.

I don’t remember which movie it was, but I do remember that I got a call from the chair of the women’s group.

She was worried.

She had just heard from the film’s production company that the print was damaged.

There was a tear in it, and it could not be projected, unless, by some miracle, we had some means of repairing it.

She wanted to know if I had the ability to make the repair.

Of course! I do that every day in the booth.

Every film print has tears, breaks, bad splices, broken sprocket holes, and I repair them as a matter of course.

So not only did the gals who booked the films for the series have no knowledge of what goes on in a booth,

but even the film’s independent production company did not understand that projectionists had access to splicers.

So there you go.

As I have said so often, the people who run the movie business don’t know anything about the movie business.

I guess it was a nice job, but the turrets were so wobbly that my zoom extender sagged and lost focus.

I decided that I hate lens turrets.

The only remedy at hand was to wrap tape around the extender and around the top of the machine to force it to be about level.

That’s why I could never get the same result twice.

Very frustrating.

There were no shutter-timing knobs on the

Cinemeccanica Victoria 8’s,

and so when the timing belt jumped a notch or two or three, what could I do?

Stopping the show was not an option.

That’s the only thing I really hated about those machines, and that was enough to make me hate everything about those machines.

One time, right near the beginning of Nashville,

I just touched the anamorphic lens and it went totally out of whack.

I couldn’t get it back into whack to save my life.

An hour later the assistant manager walked by, and I begged her to help.

She touched it up in an instant, bless her heart.

I thought I knew all the anamorphic-lens tricks, but she knew one I had never learned.

I still haven’t learned it.

On projector #1 there were mismatched parts, force-fitted together, which threw the film gate out of alignment.

Old triacetate (and diacetate!) prints could only with difficulty be wound onto platters, and they refused to be wound off of platters.

They were brittle.

They would snap into a trillion pieces, and every sprocket hole would split.

Yes, I tried it.

Yes, I tore the film to shreds and split every sprocket hole.

Yes, I was smart enough to stop before I damaged more than just a few feet of a tail.

I was not about to damage any of the film proper.

So I had to sit on the floor and turn the platter by hand to get three feet of film loose,

and then I would turn the 2,000' reel by hand to take up those three feet of loose film.

Three feet at a time.

A typical film is about 9,000 or 10,000 feet long.

You do the arithmetic.

I don’t want to.

Then rewind on the open rewinder,

and then rewind again evenly on the hand rewinder.

Then we got Il gattopardo,

which was over 16,000 feet.

After two long evenings, I gave up.

I told the series coördinators to order a replacement print.

No can do. The print under my charge was the only print in the entire USA.

Then cancel the show, I said.

No, we cannot cancel the show.

Get that film on screen, whatever it takes.

I saw that I would need to do something more extreme.

I took a day or two off from my regular job and spent a grand total of 25 hours patching that print back together,

and tearing my hands to confetti in the process, since every last sprocket hole was split.

I didn’t finish putting it together until an hour before showtime.

My clothes were drenched, I was covered in sweat, my hands were bleeding, and I decided to walk to the restaurant next door to get a glass of water.

As I was exiting the booth, the two series coördinators just happened to walk into the building.

They were quite taken aback, and one of them asked, “What happened to you?”

“I told you the film was in bad shape.”

Then after that single screening, I had to pack it up again.

16,000 feet, three feet at a time.

Oh heavens above, that took forever.

A few entire evenings, actually.

That’s when I decided that I did not merely dislike

platters, I detested them with every fiber of my being.

Platters were supposed to reduce the workload and save time?

Platters were supposed to be gentler on film?

Oh give me a break!

You’re going to tell me off for cutting my hands on the film, aren’t you?

You’re going to say that I should have worn gloves, aren’t you?

You can wear gloves on a print that’s clean and in fairly good condition.

I have tried gloves a number of times.

After just one foot of film, the gloves are shredded and black and filled with grime.

Gloves are useless when working on films that are in terrible condition.

If you decide to wear thick gloves that will not easily get shredded,

then you’ll damage the film with them.

You can’t feel most of the faults through a thick glove.

The glove will collect the grime and scratch the film,

and any hanging edges will catch and tear.

That’s why I did not use gloves when inspecting battered prints.

Now, startlingly, the image and sound on Il gattopardo were still pretty good.

There were countless thousands of splices, but most of those were just to hold torn film together.

There were lots of tears, since this print must have been run on lots of platters.

Remarkably little footage was missing.

Yet, after several exhausting days patching that movie together, making rounded V cuts on tens of thousands of bits of film edges hanging off of broken sprocket holes,

I did not catch two misframed splices.

I must have been cross-eyed by then.

I was too exhausted to project the film, and so another guy volunteered to nurse the machines that evening.

When those two misframed splices hit the screen, he framed them instantly.

I guess he didn’t want me running to the booth to tell him off again.

Note: The title, just as the title of Lampedusa’s source novel, was translated as The Leopard everywhere.

I had read, though, that gattopardo is not a leopard (leopardo) at all, but an ocelot.

An Italian set me straight: It is most definitely not an ocelot; it is a serval.

So there.

As much as a week later, the print of The Serval was still in the booth.

I asked the assistant manager why.

She said that nobody else had booked it, and so the distributor would not ask for it to be returned for another week or two.

I sent an email to the series coördinators, saying that we could run it again if they liked.

As much as I hated putting that film onto the platter and taking it off again,

I wanted to see the movie again, because it was not available on home video at the time.

No, the coördinators said, there was no way on earth to schedule another screening, public or private.

Now, let’s think about

platters.

Their origins go back to the early 1910’s, perhaps even a little bit earlier.

One forebear was called the

Toledo Non-Rewind ,

and the other was called the

Feaster No-Rewind .

Those early machines held only 1,000' of film, and their purpose was to eliminate strain on the film.

I’ve never run one or even seen one, but, from the illustrated descriptions, they look like good designs.

(See F.H. Richardson,

Motion Picture Handbook, 1915, pp. 315–321.)

Platters took that idea to the extreme.

Instead of holding only 1,000' of film, they could hold up to about 22,000' of film.

While running a film, they’re not so bad.

Loading a film onto a platter, on the other hand, damages the film, always.

There’s far too much tension on the film as it wraps around too many twisting rollers,

as the platter pulls a film off of a relatively light 2,000' reel.

Winding a film off of a platter and back onto 2,000' reels damages the film even more,

because a light 2,000' reel is pulling, usually, somewhere around 10,000' of film, often more,

around an extremely twisting path.

Here’s what I mean.

Polyestar prints can withstand the strain the first few hundred times.

Diacetate and triacetate films don’t take it too well.

If the triacetate films are just a few years old, they are brittle.

If the film is diacetate, it is an antique that is ready to crumble.

Such prints cannot withstand the strain and they fall to pieces.

On Screen #1 we had

Bird Man of Alcatraz,

and I think it was for the Great Directors series, but maybe it was for the Hollywood series.

I had not a minute to work on it, and so when I arrived at the cinema,

just in time for the show, it was already assembled onto the platter.

I decided to stick around in the booth, because I just knew something would go wrong.

Part way through the movie, I saw something from the corner of my eye.

Rising up from the platter disc, up through the tower rollers, through the air towards the machine, was a film tear.

It was not a typical film tear.

Here, let me simulate it for you:

The manager, later that night, shared with me a frame grab from the security camera,

showing my face when I realized what was about to happen:

To my amazement, the film did not break.

It just played right on through.

I could hardly believe it.

It was the only time I’ve ever seen anything like that.

On other machines, the tiniest little defects will shut down a show.

This major defect, somehow, didn’t even raise the machine’s eyebrows.

The machine was totally nonchalant about it.

Shrugged its shoulders and just kept on chugging away.

There was a great flash of white on the screen, but it just played, no prob.

I cut out those few frames after the show, so that the next projectionist would not be cursed by them.

Oh how I wished that the other projectionists would simply have inspected the prints before assembling them onto the platters.

Again, I just ask for too much.

|

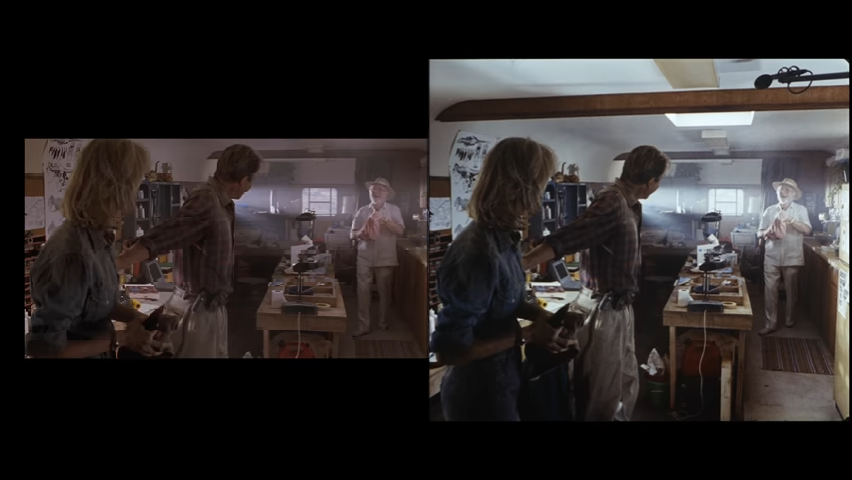

Click on the picture above and watch the video.

Someone who calls himself

CMXToonami made this extremely interesting analysis.

Apparently, parts of Jurassic Park were shot with the full Silent aperture,

but were printed as 1:1.18 MovieTone with the left side lopped off to make room for the soundtrack.

The image was composed for a 1:1.85 crop, but could also be shown at the taller 1:1.66 without a problem.

On the left is a 1:1.85 widescreen crop.

That image was pulled from a

|

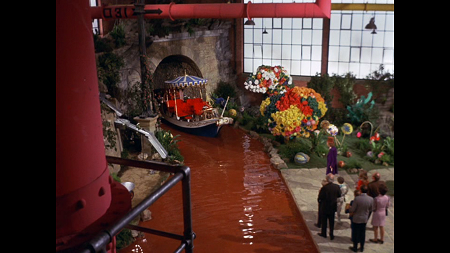

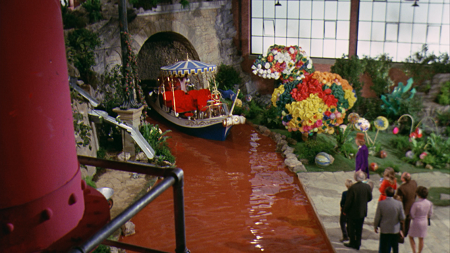

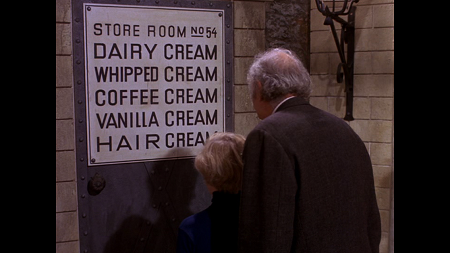

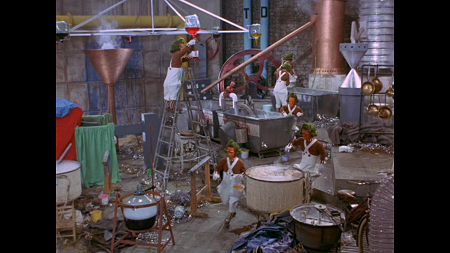

Just because everybody gets it wrong:

We ran a single kiddie matinée of that wonderful horror film,

Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (Screen #1),

and so I was finally able to get my question answered:

It was framed for a 1:1.85 crop, I think, if memory serves.

It was shot with at least two cameras,

and so half the film was shot at 1:1.375 and half was shot at the full Silent aperture.

So there.

I decided, oh what the heck, run it at 1:1.375.

It looked really nice that way.

Again, sometimes I prefer it wrong.

Sometimes it looks better when it’s wrong.

I just checked the 1:1.33 DVD against the 1:1.78 Blu-ray.

The DVD shaves off the top, the bottom, and the right, and it totally lops off the left.

The Blu-ray shaves off the top and bottom, but, in some shots, much more of the bottom than the top.

Neither is authentic.

Why can’t we just get it without any cropping?

It looked fine when I ran the 35mm print at 1:1.375.

Lovely movie.

It’s the only movie I know of that entertains children but is way too scary for grownups.

Roger Ebert,

“Movies the Way God Meant Them to Be Seen,”

Salon, Tuesday, 11 September 2001:

“Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory came at last to DVD, in August 2001.

Although it was shot in widescreen, it had its sides cropped off to make it into a 4:3 image.

A Warner Home Video spokesperson told me:

‘It is in a |

|

DVD |

Blu-Ray |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

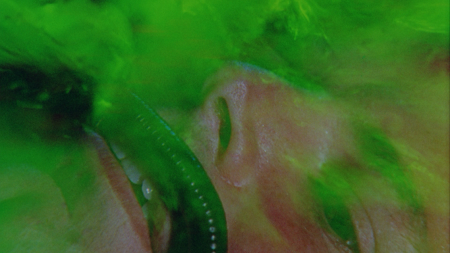

Sometimes I think the camera operators reluctantly kept the action in the 1:1.85 safe area

but made the tops and bottoms active and interesting, quite intentionally.

Sometimes I think the camera operators are jokers.

Sleeper

and

Love and Death

look perfect when cropped to 1:1.85,

but, if you are ever lucky enough to handle 35mm prints of those films,

watch what happens when you open the aperture all the way to 1:1.18 MovieTone!

Makes you wonder, doesn’t it?

I wish I could illustrate, but alas.

You want to know. Okay.

For many movies, if you open up the aperture and show more of the top and bottom,

you occasionally see catwalks and company vans and electrical wiring and Fresnel and Leko lights and microphones and sunshades and whatnot.

What do you see when you open up Sleeper?

Exactly that, except not every now and again, but all the time, every moment.

Was that intentional?

I think it was.

I don’t know for sure, but I think it was.

As for Love and Death, well, that one is trickier, and I am stumped.

It was an hour and a half of Russian jokes, including jokes about a Russian filmmaker named

Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein.

Now, Eisenstein disliked being confined to one particular image shape.

He wanted different shots to have different shapes, to match the mood and meaning.

What happens when we open up Love and Death?

Exactly that.

Every shot is a slightly different height, shape, and position.

At the end, when Boris speaks directly to the camera, his face fills the 1:1.18 MovieTone aperture.

Was that intentional?

I think it was.

I don’t know for sure, but I think it was.

(As for the current vogue of circulating ever more horror stories about Woody Allen,

be careful!)

After about two years at the eight-plex, helping friends and acquaintances get their specialty shows on screen,

I realized that it was way past time for me to give it all up, for good.

The specialty films were mostly okay, but the other screens were filled with Hollywood pabulum,

which I could feel even when I was not looking at it.

It was really getting me down.

Those Hollywood movies were poisoning my soul.

I truly resented having every Hollywood movie treat whites as the indigenous people of the US.

I truly resented having nearly every Hollywood movie treat Southern California as the only place of note on the globe.

I truly resented witnessing atrociously bad actors delivering atrociously bad dialogue in atrociously written scripts

that were atrociously directed and atrociously photographed and atrociously edited.

I truly resented the emphasis on guys/cars/guns.

A writer who can’t think of a story any better than guys/cars/guns should go back to washing dishes or digging ditches.

I truly resented having shallow, insecure characters doing nothing but shallow, insecure things

and having this presented as being of momentous significance and deep psychological insight.

I truly resented celebs and producers earning tens of millions each for each of those disgraces.

I was truly despondent that Joe and Jane Average paid hard-earned money

to help said celebs and producers make said tens of millions for each said disgrace.

I had to stop.

Maybe this wasn’t literally killing me, but it sure felt as though it was.

A thought began to form. It was vague at first, but then it grew over a few years.

Humans are the world’s only storytelling animals.

Unlike other animals that survive in extreme climates, that can run, jump, hop, hide, burrow, attack, or threaten with their gigantic teeth,

humans had no natural protection from the elements.

They were helpless — unless they could band together and strategize.

The only way to strategize was to teach, and the only way to teach was by telling stories.

Until just over a century ago, humans were master storytellers.

Then movies happened.

Then radio happened.

Then TV happened.

People no longer told stories.

They just worked in offices or on chain gangs, and stories no longer did any good.

The only storytellers were paid novelists and paid script writers, who, for the most part, were deplorably bad.

Craving stories, people flocked to the theatre, to the cinema, to the radio, to the TV set,

and saw and heard stories crafted by major corporations, or at least on behalf of major corporations,

stories designed to convince us that those in authority deserve to be in authority,

and that those at the bottom of the corporate ladder deserve no better.

The corporate stories convinced us that city life and consumerism were admirable,

and that country living and self-sufficiency were laughably outdated.

The corporate stories convinced us that police and judges and juries could do no wrong.

The corporate stories convinced us that people with odd looks, odd cultures, odd accents were not our equals, and were likely quite dangerous.

The corporate stories convinced us that eccentrics, who disbelieved that our social norms were objectively worthwhile, were foolish.

The corporate stories for radio and television were crafted to sell deodorants, to sell soaps, to sell jewelry, to sell junk food, to sell toys,

to sell barbecue sauce, to sell cars, to sell cosmetics, to sell tickets to the theatre, to sell tickets to the cinema, to sell radios, to sell TV sets.

A few of these paid storytellers were good.

They wrote good novels, they wrote good theatre, they wrote good cinema, good radio, good television.

The few were very few, very few indeed.

For the most part, movies were designed to rob us of our time, to rob us of our thoughts.

They were designed to implant new thoughts, to make us obedient to authority, to sap our imaginations,

to make us cynics incapable of believing that any change for the better is possible or even desirable.

I began to hate movies.

Well, most of them, anyway.

I am convinced that Hollywood is the fourth branch of the federal government,

functioning as a remarkably subtle US Department of Propaganda.

|

SIDE NOTE ADDED ON SUNDAY, 31 JULY 2022:

Oh my heavens!

My intuition was more than correct.

I just read David McGowan’s

Weird Scenes inside the Canyon: Laurel Canyon, Covert Ops & the Dark Heart of the Hippie Dream (Headpress, 2014).

Next to impossible to put down.

My head is spinning.

Those who follow politics realize that the Blue Bloods, who are all distantly related,

who are all either narcissists or psychopaths, who are all billionaire members of secret societies,

who are all connected with Wall Street and international banking and the military, are not part of our world.

When election time rolls around, we are usually offered the choice of voting for

one particular Wall Street billionaire psychopath who will swindle us,

or a different Wall Street billionaire psychopath who is sixth cousin of the first, who will swindle us.

It’s a depressing choice, especially now with rampant gerrymandering and ever-expanding vote suppression.

Occasionally an outsider gets in who is one of us and who sides with us — think Rashida Tlaib —

but that’s fairly rare, and such people are smeared mercilessly and are usually hounded out of office pretty darned quickly.

Much the same applies to showbiz.

We should expect people in showbiz to be a bit different, a bit eccentric, a bit creative, yes.

That is not what we find.

We find that too many people in showbiz are from the same families as the political Blue Bloods,

they are the children of officers in military intelligence and PsyOps, and they are all dysfunctional at best.

Dysfunctional?

Well, let’s take a

When you watch famous performers on stage or on camera, you can recognize a disconnect.

This was not so true for many vaudeville stars, but for more recent specimens,

it is difficult to deny that there is a communication breakdown.

While they might be pleasant during a Q&A, or while they might be courteous during a one-minute chance meeting,

you know that you will never be able to make friends with them.

They live in their own separate universe; they do not mix with mere mortals.

(Tinto was the one glowing exception,

a genuinely good guy with a genuinely warm heart who would genuinely reach out to those he recognized as special.

Despite having acquired some wealth in his 50’s, he continued to live humbly.

No mansions and limousines and chauffeurs for him. Never.

Just a little rented farm house across the street from subsidized housing.

That was enough.)

Anyway, this disconnect is something that I have recognized for decades.

I did not completely understand it, and I still do not completely understand it,

but it is a fact, a fact that cannot reasonably be denied,

just as a hungry alligator approaching you in your swimming pool poses a danger, which is a fact that cannot reasonably be denied.

That’s just the way things are.

You’re not going to change it.

I’m not going to change it.

Nobody’s going to change it.

Ever.

Well, along comes David McGowan with some

insights into this matter —

insights that turned my stomach and made me too afraid to open my door.

Now, I discover that David McGowan has published some truly nutty things.

For instance, he has published how the moon landings were faked.

I saw that and I cringed.

The space program is hopelessly beyond his area of expertise.

That is the problem of gathering tons of facts without having the requisite knowledge and background to make sense of those facts;

that’s a situation that can lead you far astray and it destroys your credibility in every other matter as well.

Should I therefore dismiss Weird Scenes?

I don’t think so.

This book has all the internal evidence of being properly researched and reasoned.

If I am wrong about that, please let me know.

For all these decades, I had erroneously assumed that the superstars of the rock world and the movie world

had done something to earn their status.

How stupidly naïve of me.

Many of them are artificial creations of military intelligence and PsyOps.

From the time I was in my single digits, I never understood the appeal of most rock music and other modern popular music.

(There’s a little bit of it that I like — very little. RHPS is tons o’ fun,

Renaissance is lovely, and a few other things are nice, too.)

To me, most rock sounds sickening, harsh, ugly, abrasive, and, say it, downright depressing.

I make my shopping as quick and seldom as possible because that rot pours forth from the PA system 24/7.

That racket gets me down.

Not a little bit down.

Way down. Way way way way way way way down.

It sucks all the enthusiasm out of me.

It’s like listening to my own premature death.

Hate the stuff.

I have long been baffled to hear people saying that it moves them.

I have long been appalled to hear people saying that it empowers them.

I have long been mystified to hear people refer to that claptrap as rebellious.

I have never heard rebellion in that noise; what I hear is reactionary.

How could anyone think such things?

Well, thanks to David McGowan, I begin to understand.

McGowan thought he would study the favorite music of his youth.

In studying it, he found all his idols smashed to dust, all his love utterly poisoned.

And I’m glad.

Witnessing that 300-page exorcism was cathartic.

The crimes that Laurel Canyon’s pop hooligans engaged in was not something I could have fathomed or invented in my wildest imagination.

It was all much worse than anything I have experienced, worse than any paralyzing nightmare I have ever had.

Yet those hooligans were all protected, and the police knew to stay away and not patrol the area.

The authorities let almost everything go, with seldom even a slap on the wrist.

Murder, kidnapping, torture, drugs galore, raping children, arson, it was all fine, as far as the authorities were concerned.

Nothing to see here.

I guess Laurel Canyon and surroundings constituted an experimental petri dish cooked up by the US military intelligence’s

Lookout Mountain Laboratory,

which stood prominently right at the top of Laurel Canyon,

and so I assume that no one was allowed to interfere with that experiment.

The Charles Manson “Family” was not an aberration in that environment;

it was not qualitatively different from anything else going on there in those years.

The stories of

Vito Paulekas (whom I had never heard of before)

and

Georgina Brayton (whom I had never heard of before)

were especially horrifying.

Why were those maniacs and their acolytes ever allowed to wander freely?

A couple times, years ago, when I got lost, I ended up driving through Laurel Canyon by mistake.

Never again. I never want to get near that place again. Never.

I had thought that Beverly Hills and Bel Air were creepy and scary.

Yeah, I visited BH a couple of times to browse the library, do research at Paley, check out an exhibit,

and then, as is my wont, I began walking around to look at the architecture and to explore the neighborhood.

Then I realized that something was deeply wrong.

I looked at the people’s faces. I looked at their clothes. I looked at their cars. Not good.

It was the same feeling you get when you go to the woods and suddenly everything gets too quiet.

I left and I have not been back.

At another time, I saw some nice woods at the north of UCLA and decided to go for a stroll to get some fresh air and to look at the trees and maybe some birds.

After a few minutes, I realized that I was in Bel Air.

I looked at the hidden gated driveways and I darted away.

In both instances, I was seized with a sudden dread fear: “I’m gonna be arrested.”

Keeping away from those places made visiting UCLA’s Powell Library and Young Library and Royce Hall a bit tricky, but hey.

But, uh, oh no, Beverly Hills and Bel Air ain’t got nuthin’ on Laurel Canyon.

Laurel Canyon is a true Hell on Earth.

One of my favorite parts of McGowan’s book deals with Miles Copeland.

You see, a few years ago I read Larry J. Kolb’s book, Overworld: The Life and Times of a Reluctant Spy (Riverhead, 2004),

because Larry was friends with Franco Rossellini and enemies with Bob Guccione.

That’s why I read the book,

which deals from first to last with “amoral” Miles Copeland, who had brought Larry into international spy work.

Now I learn from McGowan that Miles had a parallel life as a rock producer.

The two went hand in hand:

promoting punk rock and overthrowing governments.

Fits together, ¿que no?

Add to that the immense connections with military experiments in behavioral and psychological control,

and, hey, what else were you supposed to expect?

|

Furthermore, I no longer felt comfortable in that part of the world.

The FBI had frozen my bank account for suspicious activity (buying movie posters from a shop in Italy).

I convinced the banker to unfreeze my account, upon which someone else hacked and emptied my bank account, putting me into severe deficit.

I learned what people really thought of me (I was the scariest and most dangerous monster who ever lived),

and my day job, which I initially loved, now terrified me.

For five days straight, I got not a wink of sleep.

Every time I began to doze off, I involuntarily leaped out of the bed and cowered in terror on the floor, against the wall.

Five days straight.

I had no idea why.

I was not sleepy, though, but I knew this was going to catch up with me sooner or later.

I saw my doctor at the HMO, and she asked if I had had any dramatic episodes of late.

Well, where do I begin?

There was for instance the police interrogation....

She cut me off right there.

“You have post-traumatic stress disorder.”

She prescribed Xanax, and told me that it is extremely dangerous, extremely addictive,

and that she would give me only eight, and under no circumstances would she refill.

I had never heard of the drug before.

I popped one that night and I slept like a baby.

I woke up completely refreshed, which was a first for me, because I never wake up refreshed.

Over the next few weeks I took four more, and I felt fine.

I tossed the remaining three pills into the trash.

After a few months of rent-free living, I had collected $2,600 in cash, and so it was time to scram.

I asked the cinema’s assistant manager (I wish I were still in touch with her!)

if she would claim I had worked for her over the past eight years.

She said, Sure!

So, with her approval, I faked a new résumé.

Maybe it was Tuesday, 13 May 2003, maybe, I think.

I’m pretty sure it was.

Without telling my employer or my friends who were running the film series,

I packed all my things up into an ABF truck.

The ABF clerk did not want to allow me to do that, because I had not paid the $600 deposit when I had booked the truck over the phone.

“What $600 deposit?”

Without that $600 deposit, he explained, I could cancel my appointment and they will have wasted a truck.

I was totally confused, because I was there, with cash in hand, keeping my appointment.

The clerk insisted that I pay the $600 deposit immediately.

“But I’m paying the entire price, right now, in cash.”

“You have to add another $600 deposit.”

His manager came over and settled that matter, to my blessed relief.

From about six o’clock in the evening, I drove a few boxes at a time, in my Geo Metro, from one city to a neighboring city,

and then back again to grab a few more boxes.

As I was inside the truck loading boxes that evening, my Sprint PCS rang.

The caller introduced herself as Annon Adams.

She was involved with the Theatre Historical Society.

She had just learned about my research and was dying to chat with me about it.

She was even thinking of driving over for a get-together.

Well, hey, you know....

I told her what I was midst of doing and why, and I said that I was leaving for good.

I packed the last box at about eight o’clock in the morning.

It had been fourteen hours of nonstop back-and-forth, but I finished, just in time to return to work.

To my surprise, I was not in the least bit sleepy.

Actually, I had seldom felt so refreshed and energetic in my life.

I planned to leave that very evening, but my phone rang.

A group at a theatre a few hundred miles away wanted me

to give some introductory comments for a Buster Keaton movie on Saturday night.

Okay.

I agreed, especially since it had been I, a few years earlier,

who had sounded the alarm to get the cinema set up properly for older films,

and it was I who had donated the Silent apertures.

So, I finished out the week,

drove the few hundred miles to give my brief comments,

and drove back that same night.

The next day, I went to the eight-plex to use the manager’s unlisted office phone to leave a voicemail message at my day job,

saying that I would have to be gone for a while, and that I would provide an update later.

The following morning, a Monday, after fighting hours and hours of traffic to get onto the freeway, I drove far away.

Once I got to Ohio, I noticed something really bizarre.

Throughout New York State, people were always a little bit on their guard when I entered their shops.

Not in Ohio.

In Ohio, I was just any other customer.

When I got to Colorado, I noticed something even stranger.

I was walking down the street, and I saw a cop car coming the other way.

I pretended not to notice, but from the corner of my eye, I paid attention.

Unlike any experience in New York State, the cops didn’t turn to eye me suspiciously.

They just ignored me and kept on driving.

I was speechless.

When I walked into a shop where people were laughing and joking around, they didn’t clam up as soon as I crossed the threshold.

They just kept on laughing and joking around.

This was cathartic.

I loved the experience.

While in Colorado, I wrapped my office key in a page torn out of a small yellow writing pad,

on which I wrote only that I would not be returning.

I mailed that to someone I knew, and asked him to forward it to the office.

Two or three days later, my email account at work was gone, and so I knew that I was at last free from that terrifying employer.

Oddly, my employer, through my third-party, sent me my remaining paychecks — plus one more!

Was that a payoff of some sort?

I rented a storage locker and emptied the ABF trailer.

Then I kept on driving even further away, and life eventually became oh so much better.

With that fake résumé in hand, I was able to get a few brief jobs here and there,

which kept me barely afloat as that initial $2,600 dwindled to nothing.

Those psychocops didn’t realize that they had actually done me a favor.

Leaving town was the best thing I ever did.

That was the definitive end of my days as a projectionist.

Never again!

That experience taught me never to be afraid of losing a job and picking myself up and moving away and starting all over again.

It’s a painful process and slow, but it’s adventurous, and it can be done.

That was about the only time I needed to hire a tax preparer, because I had had so many jobs in so many states in 2003.

The guy at H&R Block was going batty with all my paperwork, but he eventually completed it,

and then the IRS sent me a lengthy litany of corrections together with a bill, because everything was wrong anyway.

For half a year, I was constantly searching for jobs.

Then, one day, thanks to a friend, a job searched for me.

At last, I began to settle down.

A New Jerseyan friend told me, on the phone, that he had never heard me sound so relaxed and carefree.

I was surprised, because I couldn’t detect any difference, but he must have been right,

because there was a brief spate of maybe two weeks in which some twenty-something gals took notice of me and showed interest.

First there was an American Indian who was a passenger in a car.

Apparently she told the driver to pull over into a lot so that she could roll down her window and say Hi to me.

Nothing like that had ever happened to me before.

I just didn’t know how to react. Stunned. Entirely stunned.

Then the bubbly Chinese gal at the Sprint shop was an especial delight. Ooooooo. Dreamy.

Again, I was so stunned that I had no idea how to react.

When I returned to the shop a few weeks later to pay my bill, she was gone, and the crew were all new.

I asked about her, but they had never heard of her. Darn.

I tried to look her up, but there are thousands of people with her name.

Then it all stopped.

Oh well.

By the way, a couple of years ago, I did a Google search to look up Tai and Cher and Scott Peterson.

Tai is still buddies with the Scott Peterson scumbag,

and Cher still regularly hangs out at the Defamatory Cinema.

They were my friends?

Well, we did have some laughs in the early days, and we all liked Laurel & Hardy.

Oy vey.

I gave up.

Since that time, whenever I see kids and young adults in emotional pain, I ignore them.

It’s no use.

I have learned that people who grow up being abused are suspicious only of those who treat them well.

Lost cause.

I have had to do a lot of rethinking about life.

At last, in about 2010, I made my decision:

Cut out the social life.

Just cut it out.

Once in a blue moon, I do still attend a birthday party or something,

and I do occasionally still go to lectures.

If I do talk with somebody, it’s shoptalk only.

Anything more personal than that, well, that would have to be someone truly exceptional.

Other than that, I have a cat, who is nicer to me than any human has ever been.

Cats are my only other weakness.

Cutting out the social life is odd.

For decades I was in touch with all sorts of people, in all sorts of disciplines, some of whom were quite prominent.

I remember, back in 2004, when I got a new phone after Sprint ripped me off, I entered my old contacts, one by one.

There were close to a hundred,

and nearly every last one of them was someone prominent in some profession or discipline, and some were quite well known.

That had not previously occurred to me.

When I was done, I went through the whole list again, and I was nearly dumbstruck.

How had I managed to collect all those people in my life?

Anyway, many of them have since died, and others just wandered off, and I wandered off, too.

Nowadays, I am in touch with almost nobody.

Strangely, I sort of like it this way.

Text: Copyright © 2019–2021, Ranjit Sandhu.

Images: Various copyrights, but reproduction here should qualify as fair use.

If you own any of these images, please contact me.

Images: Various copyrights, but reproduction here should qualify as fair use.

If you own any of these images, please contact me.