Chapter 20

My Very First Job

My Very First Job

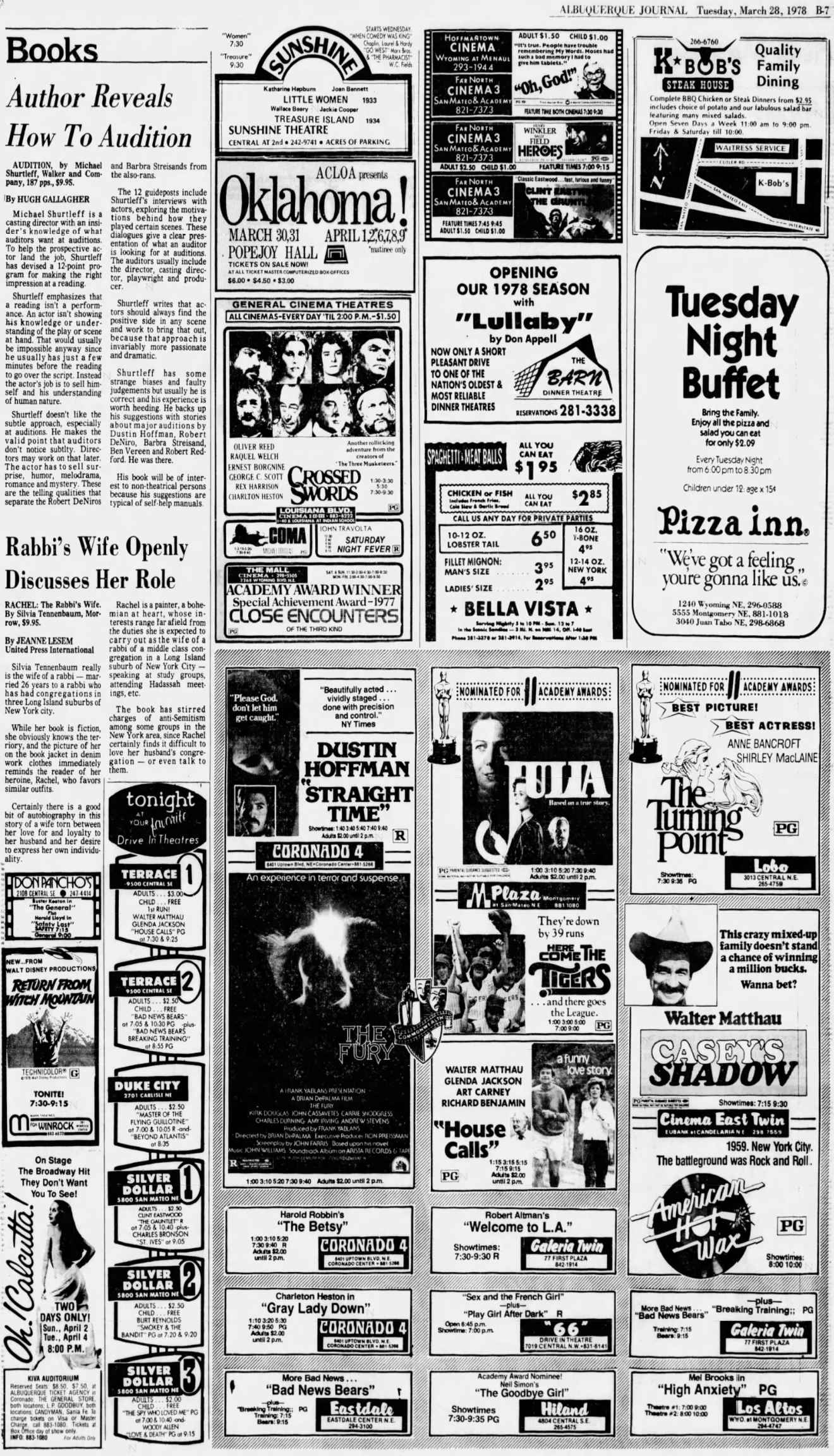

On Sunday, 19 March 1978,

I paid a visit to Bob Shaffer at the projection booth of

Los Altos Twin and he gave me a heads-up.

A projectionist at Don Pancho’s had just resigned to take a union projection job,

which meant there was an opening for me. Grab it! he insisted, right away!

Now, I attended movies on Saturdays, almost never on any other day of the week.

The next evening, Monday the 20th, was exactly when nobody would expect me to be at a cinema.

I stood in front of the closed door of Don Pancho’s and I felt like a stalker.

Ernie walked up and turned to unlock the door and was startled to see me there.

“What are you doing here?”

“Do you need a projectionist?”

“As a matter of fact, we do.”

The show that evening was Son of the Sheik,

in a color print that imitated tinting, but the left side was cropped off to make way for the music track, and

Ken Russell’s Valentino, also partly tinted, but 1:1.75 hard matte.

(Why do I relate these details?

Well, I remember them, that’s why.

Why keep these things a secret just because they have no bearing on the main story?

It’s been my lifelong compulsion to record the past.

Besides, with these clues, I was able to pinpoint the day.)

We chatted and he gave me a nice compliment:

“You’re not so much of a little kid anymore.”

I was nervous about what the owner would think of my applying after the misadventure of a few years earlier.

I think Ernie was nervous about it too.

We decided to brave it and so we gave it a good college try — and it worked!

The owner was extremely pleasant, professional, helpful, open, warm, and in good humor, and he seemed really glad to have me onboard.

He seemed like the perfect gentleman and I was looking forward to this job.

It was on that morning that I met, momentarily, for the first and last time,

the accountant, who was also the Third Business Partner, and who gave the impression of being everybody’s favorite granddaddy.

I also met, for the briefest second, the Second Business Partner, and all my alarm bells went off.

At age 17, I didn’t think things through.

I was entirely oblivious to what now to me is blatantly obvious.

Movie, Inc., had started off as a single-screen indie.

Then it took over Don Pancho’s, but I didn’t know the background story in those days.

Then it began booking for the Hoffmantown and then it leased the brand-new Screening Room Twin.

As I ponder this madness, I think I can reconstruct the thoughts of the three minds that ran Movie, Inc.

To get more clout and lower rates, it was necessary to have more screens.

That is why they thought to diversify by running more screens in Albuquerque.

They discovered that, no matter how many screens they had, there were only 50 people on any given weeknight who would attend an offbeat movie,

and only about 200 on a weekend evening, and maybe another 100 on a weekend midnight.

They could have one screen or a hundred screens, and it wouldn’t have made any difference.

There were only 50 who would attend on a weekday night, and only 200 who would attend on a weekend night.

That is not per screen. That is per night!

They were not increasing the market base, but diluting it and hæmorrhaging money.

The company was growing too quickly, far too quickly,

and I feel quite certain that purchases were made on credit, not in cash.

Albuquerque, with its minimal population and much more minimaler intellectual crowd,

could not support more than one small repertory/art house, and yet Movie, Inc.,

was running three (The Guild, Don Pancho’s, and the Hoffmantown),

and then, after the Hoffmantown venture blew up, it began running FOUR

(The Guild, Don Pancho’s, and the Screening Room I & II).

After a few weeks, the Screening Room coughed up blood and was closed.

Then The Guild was closed,

and Movie, Inc., was back to running a single screen in Albuquerque.

Then the newspaper ads got small. I mean, really small, like so small they were entirely unnoticeable

even if you were deliberately searching for them.

You know, like this:

Just leaps right out at you, doesn’t it?

That was a sign that things were not in the best financial shape.

What to do?

Diversify not by being delusionally optimistic about Albuquerque,

but rather by expanding to other cities, one cinema per city, and only one.

That is why Movie, Inc., it started buying up or leasing indie houses here, there, and everywhere.

Movie, Inc., purchased or leased

the River Oaks in Houston,

the Coronet and then

the Edison in Dallas,

the Varsity in Austin,

the Prytania in New Orléans, and

the Tivoli in St. Louis;

it was booking for other cinemas in Phoenix, Tucson, and San Diego;

and soon there would be the Memphian in Memphis

and others in Atlanta, San António, Lubbock, Columbus, and Charlotte,

and there were probably a few more besides.

Of course, as you know full well, this is not diversification.

All these are the exact same business on the exact same business model.

True diversification would have been establishing other types of business, so that when one fails, the others could subsidize it.

The Movie, Inc., type of diversification was too risky.

If the business model itself were for any reason to fail, the whole empire would capsize.

I could research this further, but I really don’t want to.

Researching this makes me feel totally empty inside.

As I look through the old newspapers online, I see other problems.

During the time that Movie, Inc., was competing against itself with three and then four screens,

it had plenty of other competitors: UNM’s SUB, the Sunshine, the Encore.

The Hoffmantown also continued to book many of the same films,

and General Cinemas Corporation and Commonwealth Amusements and Mann Theatres began their own midnight shows with the same cult favorites.

All in all, that was definitely taking a bit of the Don Pancho’s audience away.

I myself attended those rivals (not the Encore, though, to my everlasting dismay) and the auditoriums were nearly empty.

As I say, suburbs and ruins of bulldozed downtowns cannot support artsy Bohemian stuff.

That was precisely when I began my career at Don Pancho’s.

Don Pancho’s, unlike almost any other cinema in town, still had rather large crowds — fifty on a weeknight

and 200 on a weekend evening and maybe another 100 on a weekend midnight (or 238 for Rocky Horror).

This was far more than what the average cinema could pull in.

Nonetheless, it was suffering.

It had lost enormous sums of money on those stupid little ventures that any five-year-old would have cautioned against.

That, I am now certain, was a large part of the reason why my career there never became a career.

The company’s bank balance must have been sinking deeply into the red, and so nerves were surely frayed.

That was the wrong time to start working there.

Somebody was going to be the scapegoat.

I did not understand any of that back then.

|

Another useless memory:

During my brief employ, I saw a clipping in the booth, a clipping from a Houston newspaper about the River Oaks.

In that clipping was a photo of its projection booth.

I was dumbfounded.

Those machines had 2,000' feed magazines but 6,000'

|

Ernie spent maybe two hours with me, teaching me the ropes, which switches go on and when,

the little day-to-day things I had never learned before.

He expressed his surprise that I was not jumping up and down with enthusiasm, but that I was taking everything seriously.

Well, that’s what I do.

That’s how I act.

I take my jobs seriously and I take my training seriously.

He didn’t understand.

He wondered if I was having second thoughts about my very first career.

I was puzzled.

That was a bad sign, I thought.

Well, I thought right!

Still posted on the booth’s wall was

a midnight schedule from the summer of 1976,

and there was a single handwritten note, made with a blue ball-point pen in Ernie’s block-capital writing.

It was written over the entry for Peter Sellers’s The Party:

“TERRIBLE MOVIE.”

That surprised me.

“You didn’t like it?”

“No,” he said, firmly.

“You didn’t think it was funny?”

“No.”

“Not even the scene with the toilet tank?”

“No.”

I was puzzled again.

How on earth could anybody dislike that movie?

That is about the only movie I have ever seen that would appeal to nearly anybody on earth.

How could he not like it?

My first shift should have been Saturday, 25 March, and my father knew that,

which is precisely why he decided that we would all go on vacation that weekend.

He always enjoyed messing up my plans, preventing me from doing my homework so that I would flunk my classes.

That’s just who he was.

It gave him a sense of power and authority, I guess.

I was a nervous wreck.

Calling in for a vacation on my very first day of work was, I feared, a really bad idea.

Surprisingly, Ernie was perfectly okay with that.

No prob, he assured me.

There were three projectionists.

Ernie and his trusted Mark (last name forgotten by me), who had been hired only a short time before,

were the important ones.

I would be the relief, to fill in when the other two were unavailable.

Now that I had this job, I got interested in the history of Donald Pancho’s and The Guild,

which is why I spent some time at UNM’s Zimmerman Library digging through the old newspapers.

That was the primitive beginning of the essay you are now reading.

In 1978, when I was 17 going on 18, the opening back in 1961 seemed like forever ago.

Now I have a different perspective.

1961 to 1978 is, in my mind, the span from before the beginning of the universe to the modern age,

yet it is the same as the span from 2001 to 2018, and, in my mind, those latter two numbers are identical.

It’s amazing how our perspectives change.

Shortly before I began my new career, a brother/sister team had begun their new career at the concession stand.

They were about my age and we never said anything more than Hi.

As soon as I got my new job, Ernie, leaning on the inspection bench, told me that if I wanted to secure my position,

I should start dating that new gal.

I was confused and shook my head and quietly said No.

“No? You’re not interested?” No.

To this day, I cannot figure out if that was a joke, if that was a test,

if that was an honest recommendation, or if that was an order.

The brother/sister team lasted only another few weeks and then they were gone, and I bet they were glad to be gone.

Now that my elders have all passed away, I can say something more.

All my jobs over the next quarter of a century were action replays of home life.

My father treated different members of our family differently.

When my first sister was around, he was much more pleasant,

and he tried to bond with her, going out to eat with her, biking, playing tennis, and so forth.

My father convinced my first sister that my mother was mentally ill.

When my first sister was not around, he was much more scary.

When my second sister was around, he was terrifying.

When he didn’t think we kids were around, he was a monster to my mother.

He was often monstrous to me.

When he didn’t think there were witnesses, he was horrifically violent to animals.

My mother had married him to escape her abusive family.

There was no escape, and her controlling and lunatic mother followed her around everywhere,

dragging her own mother along as well.

Granny had been a nonpracticing Greek Orthodox until 1966, when she suddenly became a fanatic.

For those of you unfamiliar with Eastern Orthodoxy,

here’s the tiniest taste.

That helps to explain the atrocities that the Russians committed in WWII

as well as the horrors of the breakup of Yugoslavia

and the current war crimes being committed by Russian troops in Ukraine.

Granny tried to arrange my marriage when I was six,

but later she changed her mind and decided that I would be a monk, no ifs, ands, or buts.

Family life degenerated into screaming fights about religion.

And then it got so crazy that I literally went crazy.

By the time I was eleven, I wished my father would just die already.

I wanted nothing further to do with him.

And then, on occasion, he was really nice to me, sometimes for as much as fifteen minutes or so,

before he would revert to his usual battery of insults.

Somewhere deep inside him there was a vestigial hint of tenderness, but he always smothered it again.

One result of this is that I did not know how to socialize.

I had friends at school and thought it was fun to make fun of them, to put them down.

After Donald Pancho’s came crashing down to an end, I poked the same fun at friends I made at work.

It is embarrassing now to watch YouTube videos about narcissistic personality disorder,

because, step by step, every behavior that those videos detail are behaviors I exhibited in my teens and twenties.

In my case, though, it was learned behavior, not natural behavior.

It was a really long time before I learned how to treat people properly.

As for my mother, she had lost all confidence in herself

and she never felt comfortable with anybody except for two stray cats who decided to adopt her,

and whom she adored with all her heart.

She had a few acquaintances, but she could never bring herself to get to know anybody.

When she would stay with me for a few months or a year or so,

I would take her out to social events and lectures and tours and so forth,

and everybody took an instant liking to her.

Then she refused to go anymore.

She didn’t say why, but I could tell it was because she didn’t think she was good enough for those people.

A byproduct of this upbringing is perfectly predictable, though I do not know how to explain it.

Every job I had was a repeat of home life.

The only people who wanted to hire me were Xerox copies of my father —

until 2003, when I finally got a job that was somewhat sane, with nice people in charge.

Heaven on earth!

So, in a nutshell, Donald Pancho’s was a traumatic experience for me.

I desperately, desperately, desperately wanted to fit in,

because I did not realize that Donald Pancho’s was a madhouse.

My first shift, symbolically, was April Fools’ Day, 1978,

with a double feature of The Kentucky Fried Movie

and What’s Up, Tiger Lily?

It went well.

No faults with the films. No mistakes. Easy.

Then Forbidden Planet

with Freaks (Sunday, 2 April),

and Black and White in Color with

Oh, What a Lovely War! (Saturday, 8 April),

and an extended run of Outrageous!

with the enchanting Hollis McLaren (Saturday, 15, through Sunday, 23 April).

It was all easy, delightfully easy.

I made but a single mistake, and it was a doozy: I neglected to latch the feed reel to the beginning of Outrageous!

Oops. Dumb. Superdumb.

Other than that, though, no problems. The prints were fine. I made no other mistakes. Perfectly smooth.

It did not remain easy and nothing would ever be smooth again.

Mark made sure of that, and I don’t think he was alone in that decision.

|

If you’re curious, no, The Kentucky Fried Movie did not have the duplicated tail at the end of Reel 2,

nor did it have the duplicated SMPTE leader at the beginning of Reel 3.

They were not there when I later saw the movie at the Hiland, either.

Projectionists chopped those out, despite the instruction to leave them in.

They were gone by the time I got the movie.

I have never seen them. I doubt they are on the DVD, but I do not know and shall probably never bother to find out.

See Topic: “9” Reel 2 Changeover Confusion,

|

Just after I started, a very nice, soft-spoken African-American gent

walked into Donald Pancho’s before the show to say Hi

to Mrs. Lela Abbin,

or Mrs. A, as we all called her.

She was the elderly ticket taker/concessionaire who had worked there since 1961.

Ernie explained to me that this gentleman had been a projectionist under a previous management,

but that the owner disliked him intensely and would not allow him to visit the booth.

He seemed to be liked — and most likeable.

I remember that Ernie introduced us:

“This is _____,” he cheerily told me.

Blank. _____. Who was _____? I tried to remember. Oh how I tried. I failed.

I tried for years to pull up a memory to fill in that _____, to no avail,

but when I began my research for this page, I ran across the name Edgar Lowrance, as you saw above.

My heavens! That was his name!

“This is Edgar.”

Except, as I now discover, the Edgar I met was not Edgar Lowrance.

He was a different Edgar.

In honor of my getting my first job, my father decided to do something nice for my first supervisor.

He told me that he would like to give Ernie a ride in a Cessna.

Let me back up.

My father had been in the RAF during WWII, and now, in his mid-50’s, he got nostalgic.

He got a pilot’s license, and when he could scrape the money together, he would rent a Cessna for a few hours,

just for the joy of being up in the air.

My supervisor accepted the invitation, and up they went.

Let me back up a little more.

My family had essentially no friends — and zero social skills.

My father was a raging volcano of anger and bad temper.

Everything disgusted him, and at home he never said anything unless it was a put-down or insult or other sort of verbal attack.

Nobody in my family had mastered the art of conversation.

My father would not converse. He would rant.

Dialogue was unheard of in the household.

Instead of dialogue, there was diatribe.

He repeatedly blew up when he would go on for two sentences without getting a reaction from me.

He shouted that I was not listening.

I protested that I was listening.

He wanted me to prove it by saying Yes, Uh-huh, Um-hmm, Okay, at the end of every sentence he uttered.

So that’s the habit I developed, and that’s the habit to which I still revert when I encounter people who like to go on at length.

Now, once in a while, especially with a stranger, my father would attempt to be pleasant, but he was far too awkward ever to succeed in that endeavor,

and so most people simply squirmed to get away from him.

Ernie never told me what had transpired in the airplane over that hour or two.

I cannot imagine what had happened.

I don’t even want to imagine.

Maybe everything was nice. Who knows?

Shortly into my tenure, I received my first paycheck.

I was sitting by projector # 2 and Ernie stepped over to me and handed it to me personally.

It was for a whopping $25 or thereabouts.

“Don’t spend it all in one place,” Ernie cheerily advised me.

I could not tell if he was being sincere or sarcastic.

I still cannot tell.

What I could discern, easily, was that he had something on his mind.

I did not know what.

I would find out within about two months.

With the second paycheck, I was able to get an eye exam and a pair of glasses.

I had never worked up the courage to ask my father for such luxuries.

His Vesuvian temper would have trebled, and I did not wish to witness it.

Ernie kindly drove me to the optometrist.

(Can’t remember which one, certainly the eastern part of the city, not far from Central, north side of whatever east-west street it was on.)

The whole experience was remarkably brief and it cost, if memory serves, a mere $75,

which, to me, was infinite wealth, and which all vanished in a moment.

My first day wearing glasses (Saturday, 5 May 1978, A Streetcar Named Desire and Last Tango in Paris),

I could see, from the booth, something I could never see even from the front row: focus drift!

Yes, in some prints, the drift is egregious and even the half-blind can see it.

In most prints, though, the drift is so slight that nobody can notice it, but it is always there.

That first day, and only that first day, I could see it, no matter how slight it was.

Only out of fear of daddy’s earth-shattering temper tantrums,

I never let family or friends know about the glasses until I moved away from home at age 24.

Odd household I had.

Oh so odd.

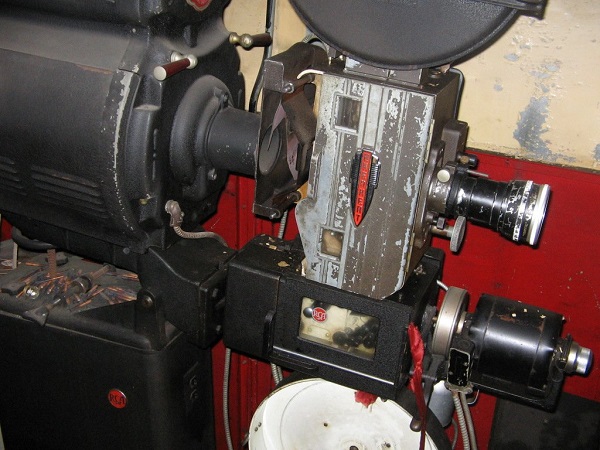

Even trivialer trivial trivia:

Donald Pancho’s had long had mismatched models of Brenkert picture heads atop Simplex SH-1000 sound heads.

My memory is vague, but after years of pondering, it finally comes back to me. It was a

BX-60 on projector #1 and a

BX-40

on projector #2.

What had probably happened was that somebody damaged a

BX-40 ,

and so management sent off for a replacement,

but by then Brenkert was out of business.

The closest available model on the used market was a

BX-60 .

Just a guess. Good guess? I don’t know.

I remember being at HQ with Ernie.

He was having a conversation with the owner, and I can’t remember the details.

What I do remember is that the owner told the projectionist to make a call

and to explain that we had Brenkert picture heads at Don Pancho’s.

“Let him laugh at you,” said the owner, but just state the facts and get this job done.

Was a Brenkert a joke?

I hardly thought so.

Oh, I think I should point out that, among the cinemas that had no instruction, installation, or parts manuals for any of its machines, were:

Donald Pancho’s,

The Guild,

the Sunshine,

the Sunset,

the Frauenthal.

Actually, of the countless booths I have visited,

almost none had any manuals.

In those days, I had no idea where to find manuals.

I would have devoured them had I been able to find them.

|

JUST FOR FUN. I just ran across some photos of Brenkert/RCA

“(former) York Theater,” Pullen Computing Services, Inc., 29 May 2008. RCA pedestal; Brenkert Enarc lamphouse; RCA 2,000' magazines; the incomplete picture head is, I think, a Hard to tell, but I would guess that the anamorphic lens is by Bausch & Lomb.  “#brenkert photos & videos,” PicDove, 23 January 2017. A cosmetically better machine. We can get a better view of the pedestal and the Enarc. Not sure, but I think the picture head is a The sound head still has the cover over the motor, but the flywheel knob is missing. The extender screwed onto the front of the lens is, I think, a zoom attachment. I’ve been trying for years to remember what that was called. I had something like that, but I gave it away. It’s probably been trashed by now. This projector was found in a junk shop. A junk shop. A junk shop. What has the world come to? You might also enjoy Tom the Wom’s collection of photos. He has more over here, including this nice illustration of the most imposing Brenkert |

When a part in Brenkert #1 got loose (again), the guys decided not to repair it.

They used that minor problem as a pretext to get rid of that machine.

They drove over a Super Simplex from the temporarily closed Guild to replace it — not the way to do things.

They all hated Brenkert.

I liked and still like Brenkert.

Yes, it’s complicated, but it’s built like the Rock of Gibraltar and nearly all the parts will last until the Second Coming, or even the Third.

Besides, Brenkert gives a perfectly steady picture, which most other projectors don’t.

The guys at Donald Pancho’s and The Guild all preferred Simplex — and they worshipped Century because of its simplicity.

They did not seem to care that simplicity came with a hefty price — in terms of film damage and compromised presentations.

I have no use for Century, and, though I like Simplex, and though I have serviced Simplex and could still do so with my eyes closed,

the earlier

“Regular” and

“Super” model picture heads were nightmares.

For instance: Taper pins to secure sprocket wheels! Good grief!

For most of my brief time as an employee, we had a Super Simplex on projector #1 and a Brenkert on projector #2.

When I mentioned this to other projectionists, they thought we were all crazy.

They were right.

Of course, because the Simplex’s apertures were undercut (.800" for 1:1.66, 1:1.75, 1:1.85, and 1:2.00),

we had to file them out to .825" to match the Donald Pancho’s screen.

I think the undercut 1:2.35, at .715"×.780", was left alone. Close enough.

Now, what would happen when we carted that machine back to The Guild?

Well, I don’t think it was ever carted back to The Guild.

Whoops! I just remembered something else!

The Brenkerts

and the Super Simplexes all needed some serious service.

They had massive leaks that spread oil onto the film.

The more often we ran a film, the oilier it got.

We put large pans underneath each projector to catch dripping oil, and padded those pans with lots of paper towels.

The guys all thought that was perfectly normal.

It was most definitely not normal.

A few drops here and there is normal, yes,

because the machines have pressure releases,

and, of course, the Super Simplex is not entirely enclosed, which is why some leaking from the gear side is inevitable.

Nonetheless, oil should never get onto the film and it should not soak the floor.

I never had that problem at any other cinema.

Someone had even added steel spouts to the Super Simplexes and the guys thought that those were part of the original machines.

When I mentioned that the projectors should not leak,

the response was to point to the spouts and say that even Simplex itself built drainage spouts into the machines

and, ipso facto, the leakage was by design.

There was no way to win that argument.

Another memory comes back, in late November 2021:

Just as I began my career at Donald Pancho’s, I witnessed Ernie inspect a print.

He put the reels on the motorized rewinder and leaned his left elbow on the inspection bench.

He ran the film between his index finger and his thumb, but he did not feel the edges, he did not feel the sprocket holes.

He ran the image through his index finger and his thumb, a practice that reveals almost nothing and that damages the film.

He was talking with me and looking at me, not at the film, as he merely counted the splices that passed through his fingers.

He did not inspect any part of the reel. He did not inspect it at all.

That was his idea of an “inspection,” and I was worried sick, because that was a print I was assigned to project!

I knew that this would be a disaster — and I was wrong, that one time.

By some miracle, the print ran just fine.

Now, two and a half years previously, that is not at all how Ernie taught me to inspect films.

Not at all.

He had been quite meticulous in the autumn of 1975.

He was now something other than meticulous.

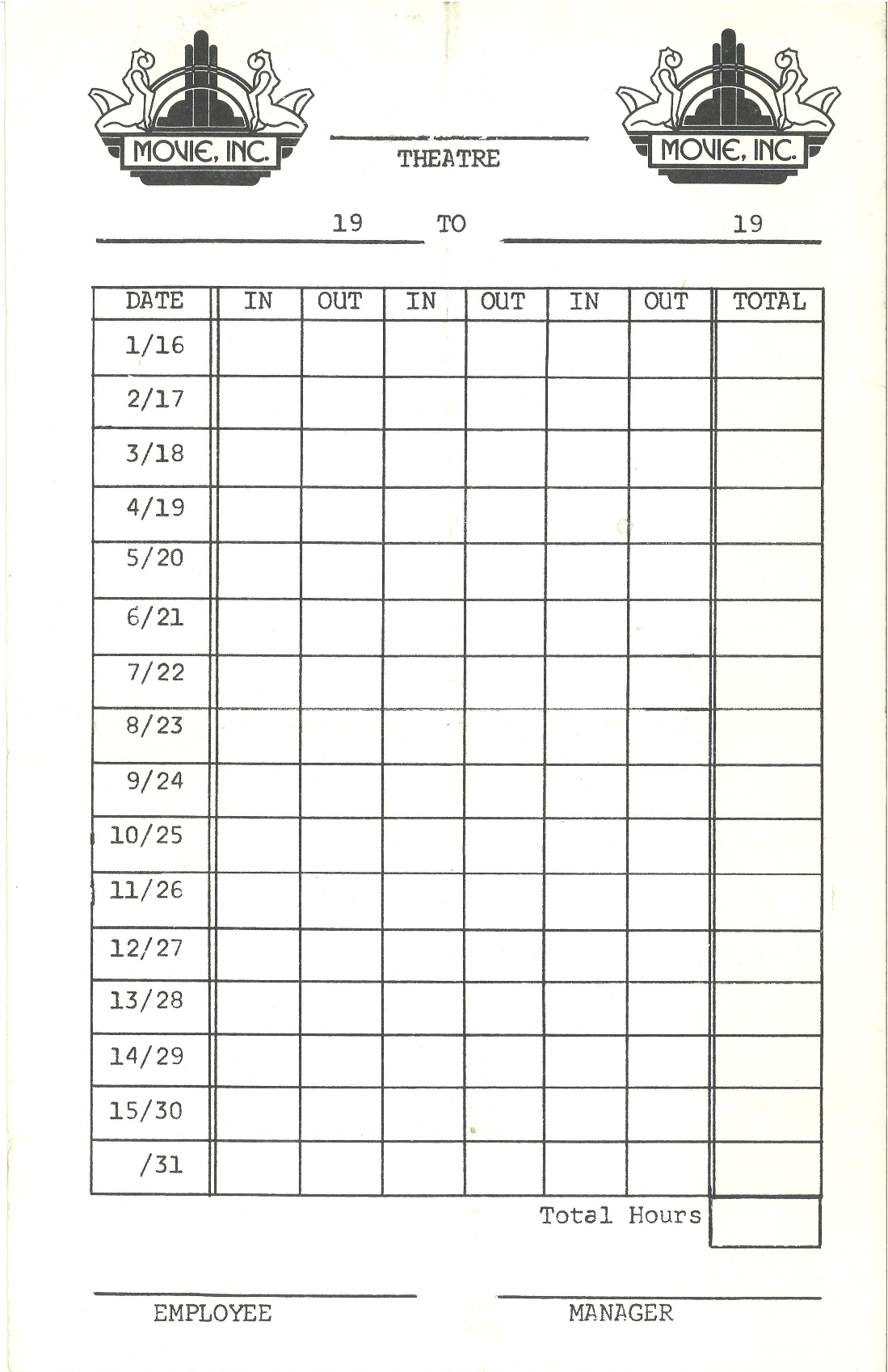

And now, even though this is of no relevance whatsoever,

I am compelled to document it, only because nobody else would ever record this:

Here is a sample of a blank time sheet:

Ernie drove me over to The Guild and showed me a cardboard box filled with brand-new

Kollmorgen Super Snaplite lenses,

not in their original little boxes, but loose, each one in a clear plastic bag, if my memory is right.

I wanted to check the focal lengths to see if we could use them for the Academy, MovieTone, and Silent formats, but he refused to let me check.

The box of lenses stayed in storage, I think, somewhere in the building.

He also took me to the little basement underneath the stage, which can be reached only from the back alley.

Inside was a

Simplex E-7 picture head, but it was missing lots of parts.

He boxed it up and shipped it off to a repair house in Colorado,

which soon enough shipped it back, having done no work on it at all.

As for that box of lenses, it may be there to this day, for all I know.

Ditto for the E-7.

On Thursday, 21 October 2021, I decided to take a few photos.

I wanted to see the backs of the buildings again.

So below is an image of the back of 3401 Central Avenue NE.

In 1942 it had been Campbell’s Food Store,

and by 1949 it was Frank’s Food Store.

In 1953 it was a stop-gap office for D&D Buick Co.

By 1956 it was Mr. & Mrs. J.T. Mason’s United Rent-All.

By 1964 it was Nash Office Machines.

By 1972 it was unfortunately a porno cinema called the Hollywood,

then the Backdoor II, and finally the Pyramid, controlled at least part of that time by Pat Baca.

I wonder if the X-shaped security bars over the windows are a legacy of his reign.

When we mosey a bit further up the alley, we see the backs of 3403 (on the right, now Il Vicino pizzeria)

and 3405 (The Guild, in the middle).

The door by the NO PARKING sign takes you to that microscopic, unfinished, windowed room,

where the incomplete Simplex E-7 was hidden away.

Ernie likely pointed out to me the writing to the right of the doorway:

CHINESE VILLAGE 3405, but if he did, I didn’t pay it no never mind. Foolishly.

Now it means a great deal to me indeed!

There was a left-over poster of Don Pancho himself, riding his burro (black background, yellow outlines).

I took it home, since nobody wanted it anymore.

I went through my files in storage recently, and it was gone.

Hope I find it again.

To my surprise, I found another item of which I had no recollection.

It was a similar sign, in the same black-yellow colors, but without Don Pancho riding his burro:

This puzzles me. When was it printed, and for whom? And by whom? It says “Art” rather than Arts, which would make this seem it belonged to the Art Theatre Guild of America Days, but it says “Theater” with an er rather than an re, which would make this seem that it belonged to the Frank Scheer days.

There was one lamphouse at Donald Pancho’s that had a peculiar anomaly.

I think it was lamp #1.

Whenever we struck it, the booth suddenly reeked of popcorn.

I never understood why.

In the wall cabinet on the western side of the booth there were two cans, each with a 2,000' reel.

I had never noticed them before, and so I assume they had not been there in 1975.

What movie was it?

It was an abridged sound reissue of Tillie’s Punctured Romance,

left side cropped off to make way for the variable-density music track.

It was a nitrate print.

I did not know it then, but I know it now: This was the

Walter A. Futter version originally issued in 1939.

Then, not long after I first saw those cans, the owner walked off with them,

presumably to show that film at the River Oaks cinema in Houston.

Whatever became of that print, I do not know.

(Now that I think about it, I bet that the Don Pancho’s owner did not realize that the print was nitrate,

I bet he didn’t know what nitrate was,

and I bet he had never even heard the word.

As for me, I would not run nitrate under any circumstances.

When it was new it wasn’t so bad.

None of it is new anymore, and so projecting it is suicide.)

|

Oh. Sorry. You don’t know what

nitrate is.

It was

an early type of film stock

that

shrank rapidly,

that got

brittle rapidly,

that was

chemically unstable,

that was

highly inflammable,

and that, upon aging a little bit, became

explosive.

A film exchange housing nitrate prints could easily go off like a bomb and burn the skin off of the neighbors four blocks away.

Yes, that really happened.

There are countless true stories of entire audiences being burned to ashes when films caught fire.

There is an entirely false but widespread belief that nitrate had richer silver content.

No, the silver was in the emulsion, not in the nitrate base.

There is an entirely false but widespread belief that nitrate films were sharper and clearer.

No, the sharpness and clarity stemmed from superior processing.

I have seen some nitrate films projected, and they looked abysmal.

They were probably rejects, too poor to be sent to cinemas, that were donated to archives instead, in exchange for tax

I just now (June 2022) learned something horrifying.

Michael Binder’s book on A Light Affliction: A History of Film Preservation and Restoration (Lulu: 2014)

contains a series of scandalous stories on pages 15 and 16:

“In America, the Projectionists’

Union objected to the introduction of safety film because they felt it

threatened their importance. Nitrate required special skills to deal with...”.

There was also a studio objection to the use of acetate film:

“...if films did not have to be exhibited under carefully regulated

conditions in licensed premises, then any movie fan with a projector

could acquire a copy of a film on safety stock and show it to anyone he

liked. The American industry feared a black market developing which

could cut into their profits...”

“In France, a similar campaign launched

by Pathé, who believed they had solved the problem of poor quality

safety film, was repeatedly blocked as production companies balked at

the potential monopolisation of film stock. It seemed to be in the

studios’ best interests to stick with nitrate despite its inherent problems

because, as author Brian Winston states, ‘The business protection that

this provided was worth the odd projection-booth conflagration.’”

Before I knew better, I lusted after nitrate.

I dreamed of nitrate.

I dreamed in nitrate.

Then I handled some nitrate footage, and my old dreams crumbled to dust.

It’s worthless junk.

Preserve the image and audio (and the leaders and the tails and the edge codes), and then let the originals rot.

Dispose of them safely.

If you have some nitrate film in your garage or in your attic or in your basement

or in your closet or under your bed, don’t touch it.

Call an archive.

If you can’t find an archive, write to me.

Please.

And please watch the video below. Please.

|

Text: Copyright © 2019–2021, Ranjit Sandhu.

Images: Various copyrights, but reproduction here should qualify as fair use.

If you own any of these images, please contact me.

Images: Various copyrights, but reproduction here should qualify as fair use.

If you own any of these images, please contact me.